Dr. José Manuel Rodriguez Delgado

Delgado was born in Ronda, Spain in 1915. He received a Doctor of Medicine degree from the University of Madrid just before the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, in which he served as a medical corpsman on the Republican side. After the war he had to repeat his M.D. degree, and then took a Ph.D. at the Cajal Institute in Madrid. In 1946 he began a fellowship at Yale, and was invited by the noted physiologist John Fulton to join the department of physiology in 1950. In 1974, Delgado returned to Spain to help organize a new medical school at the Autonomous University of Madrid.

Delgado's research interests centered on the use of electrical signals to evoke responses in the brain. His earliest work was with cats, but later did experiments with monkeys and humans, including mental patients.Much of Delgado's work was with an invention he called a stimoceiver, a radio which joined a stimulator of brain waves with a receiver which monitored

E.E.G. waves and sent them back on separate radio channels. This allowed the subject of the experiment full freedom of movement while allowing the experimenter to control the experiment.The stimoceiver could be used to stimulate emotions and control behavior. According to Delgado, "Radio Stimulation of different points in the amygdala and hippocampus in the four patients produced a variety of effects, including pleasant sensations, elation, deep, thoughtful concentration, odd feelings, super relaxation, colored visions, and other responses." Delgado stated that "brain transmitters can remain in a person's head for life. The energy to activate the brain transmitter is transmitted by way of radio frequencies." (Source: Cannon; Delgado, J.M.R., "Intracerebral Radio Stimulation and recording in Completely Free Patients," in Schwitzgebel and Schwitzgebel (eds.))

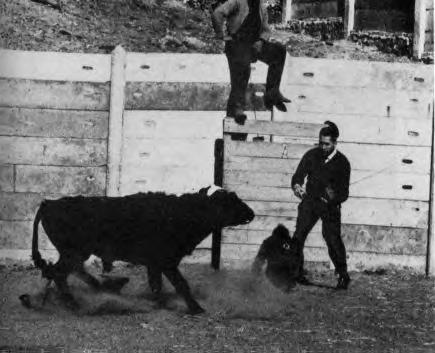

The most famous example of the stimoceiver in action occurred at a Cordoba bull breeding ranch. Delgado stepped into the ring with a bull which had had a stimoceiver implanted. The bull charged Delgado, who pressed a remote control button which caused the bull to stop its charge. Delgado claimed that the stimulus caused the bull to lose its aggressive instinct. Although the bull incident was widely mentioned in the popular media, Delgado believed that his experiment with a female chimpanzee named Paddy was more significant. Paddy was fitted with a stimoceiver linked to a computer that detected the brain signal called a spindle. When the spindle was recognized, the stimoceiver sent a signal to the central gray area of Paddy's brain, producing an 'aversive reaction'. Within hours her brain was producing fewer spindles.

MIND CONTROL

José Delgado Controls An Angry Bull

by Electrical Stimulation of the Brain

New York Times report (1965)

"The individual may think that the most important reality is his own existence, but this is only his personal point of view. This lacks historical perspective. Man does not have the right to develop his own mind. This kind of liberal orientation has great appeal. We must electronically control the brain. Someday armies and generals will be controlled by electric stimulation of the brain."

Dr José Delgado, Director of Neuropsychiatry Yale University Medical School Congressional Record, No. 26, Vol. 118 February 24, 1974

Dr José Delgado began his investigation into electrically stimulated pain and pleasure in Spain during the 1930s. He later became Director of Neuropsychiatry at Yale University Medical School, where he refined the design of his remote-controlled "transdermal stimulator". Dr Delgado discovered that a whole range of emotions and behaviours can be electrically orchestrated in humans and non-human animals alike. The individual has no capacity to resist such control if stimulated.

Dr Delgado had great faith in his technology. In one famous experiment conducted in Spain, Dr Delgado confronted a charging 1,000-pound bull. As the horned animal lunged towards him aggressively, Dr Delgado used a radio signal to activate an electrode implanted deep in the bull's brain. The bull was brought to a halt at Delgado's feet.

In Journey Into Madness, The True Story of Secret CIA Mind Control and Medical Abuse (Bantam Books, 1989), Gordon Thomas, the former BBC producer, foreign correspondent and investigative journalist, relates how "Dr Gottlieb and behaviorists of ORD [Office of Research and Development, CIA, Central Intelligence Agency] shared [Dr.] José Delgado's views that the day must come when the technique would be perfected for making not only animals but humans respond to electrically transmitted signals" ... "Like Dr Delgado [Yale University], the neurosurgeon (Dr Heath of Tulane University) concluded that ESB [electronic stimulation of the brain] could control memory, impulses, feelings and could evoke hallucinations as well as fear and pleasure. It could literally manipulate the human will - at will."

When Jose Delgado and a few other intrepid scientists first began exploring the effects of implanting electrodes in the brain half a century ago, they could not foresee how many people would one day benefit from this line of research. By far the most successful form of implant, or “neural prosthesis,” is the artifi cial cochlea. More than 70,000 people have been equipped with these devices, which restore at least rudimentary hearing by feeding signals from an external microphone to the auditory nerve. Brain stimulators have been implanted in more than 30,000 people suffering from Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders (including 17-year-old Kari Weiner, shown at the right). Roughly the same number of epileptics are being treated with devices that stimulate the vagus nerve in the neck. Work on other prostheses is proceeding more slowly.

Clinical trials are now under way to test brain and vagus nerve stimulation for treating disorders such as depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic attacks and chronic pain. Artifi cial retinas—light-sensitive chips that mimic the eye’s signal-processing ability and stimulate the optic nerve or visual cortex—have been tested in a handful of blind subjects, but they usually “see” nothing more than phosphenes, or bright spots.

Several groups have recently shown that monkeys can control computers and robotic arms “merely by thinking,” as media accounts invariably put it—not telekinetically but via implanted electrodes picking up neural signals. The potential for empowering the paralyzed is obvious, but so far few experiments with humans have been carried out, with limited success. Chips that might restore the memory of those affl icted with Alzheimer’s disease or other disorders are still a year or two away from testing in rats. The potential market for neural prostheses is enormous. An estimated 10 million Americans grapple with major depression;

4.5 million suffer from memory loss caused by Alzheimer’s disease; more than two million have been paralyzed by spinal cord injuries, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and strokes; and more than a million are legally blind.